Strange Days

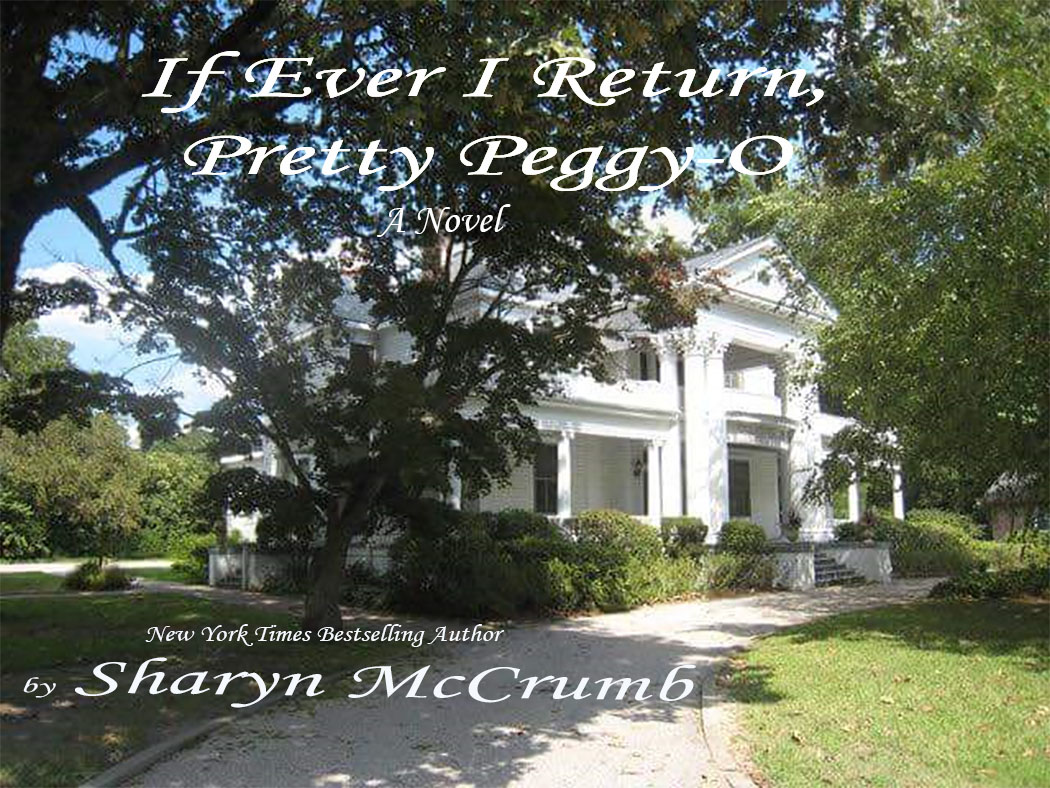

This attempt to make sense of the inexplicable by making up my own "legend" is still an occasional source of inspiration to my work, most notably in the novel If Ever I Return, Pretty Peggy-O, which began as an attempt to answer the question: "I wonder who lives in that house." That house is a stately white mansion set amid stately oaks on Highway 264 on the outskirts of Wilson, North Carolina.

My parents lived in Greenville, North Carolina, and practically the only way to reach Greenville from points west was to take Highway 264, which meant that I had been I had been driving past that white mansion for nearly twenty years: home for weekends from UNC Chapel Hill, back from my job as a newspaper reporter in Winston-Salem, and later back from the Virginia Blue Ridge, where my husband and I were attending graduate school at Virginia Tech.

In the spring of 1985 I was driving home by myself when I passed the big white house on Highway 264, and I said for at least the two hundredth time: "I wonder who lives in that house." I still don’t know who really lives there: it isn’t the sort of place that invites drop-in visits from inquisitive strangers. I decided to answer the question with my imagination. "A woman lives in the house," I thought. "She bought the house with her own money. She didn’t marry to get the house, and she didn’t inherit it. Who is she?" A folksinger. She would have to have made a substantial amount of money to be able to buy the house, but in order to take up residence in a small Southern town, her career would have to be over.

"McCrumb draws you close, makes you care, leaves you with the sense, sought for in most fiction, that what has gone on has been not invention but experience recaptured." - Los Angeles Times

"A masterful tale of suspense . . . This fine novel is the product of a gifted and accomplished writer." - Steven Womack, Nashville Banner

"Sharyn McCrumb, like every fine writer, has an abiding sense of place, a deep understanding of her world and the forces, human and otherwise, that shape it." - San Diego Union-Tribune

A character began to take shape. This folksinger had attended UNC-Chapel Hill in the Sixties, as I had. She was still young-looking, a trim blonde woman in her early forties, who had once been a minor celebrity in folk music, but her popularity waned with the change in musical trends, so now she has bought the white mansion in the small Southern town, looking for a place to write new songs, so that she can stage a musical comeback, probably in Nashville. She doesn’t know anybody here, I thought.

I had loved folk music when I was in college, and I had grown up listening to my father’s mixture of Ernest Tubb and Francis Child, so I began to consider what songs this folksinger character might have recorded. Since I was alone in the car, I could sing my selections as I drove along. After a couple of Peter, Paul, and Mary tunes, I happened to recall an old mountain ballad called Little Margaret. I was reminded of it, because I had heard Kentucky poet laureate Jim Wayne Miller sing it in a speech at Virginia Tech only a few weeks earlier. The song is a Child Ballad. It is four centuries old, and it is a ghost story. Little Margaret sees her lover William ride by with his new bride, and she vows to go to his house to say farewell, and then never to see him again. When she appears like a vision in the newlyweds’ bed chamber that night, William realizes that he still loves her, and he goes to her father’s house, asking to see her: "Is Little Margaret in the house, or is she in the hall?" He receives a chilling reply: "Little Margaret’s lying in her cold, black coffin with her face turned to the wall."

I sang that verse a few times, because some instinct told me that the heart of my story was right there. The owner of the house is a folksinger. She has moved to a small town, where she doesn’t know anybody, and one day she receives a postcard in the mail, with one line printed on the back: "Is Little Margaret in the house, or is she in the hall?" The folksinger’s name is Margaret! The line would terrify her with its implied threat, and she would take the message personally, because her own name was in the line. Having sung the song many times in her career, she knows the next line: "Little Margaret’s lying in her cold, black coffin with her face turned to the wall." I pictured her calling the local sheriff in a panic, and saying that someone is threatening her life, but the sheriff sees no threat in the line on the postcard. He tells her that the message is simply a prank. I thought: Suppose something or someone close to her is violently destroyed that night. Then she will know that the threat was serious. Then all she can do is wait for the next postcard to come, as she and the sheriff try to find out who is stalking her.

As I drove toward my parents’ house, I followed the thread of the plot, so that by the time I reached Greenville, I knew who lived in that house, (which I had mentally relocated to east Tennessee), and I had the seeds of the first Ballad novel If Ever I Return, Pretty Peggy-O. That hour of inspiration was followed by several years of hard work, researching the high school reunions of Sixties’ graduates, talking to Vietnam veterans, and interviewing law enforcement people, but the idea itself came from an old mountain song.

The theme of If Ever I Return, Pretty Peggy-O came from a more modern melody: the Doors’ tune Strange Days Have Tracked Us Down. I thought: Suppose "strange days" tracked everybody down one summer in an east Tennessee village. For the Baby Boomers it is their 20th high school reunion, forcing them to come to terms with their shortcomings; for the sheriff and his deputy, it is the memory of Vietnam, which haunts them both but for different reasons; and for Peggy Muryan, the once-famous folksinger, strange days track her down in the form of a stalker who still remembers her days of celebrity. For Appalachia itself, the Strange Days refer to the time when the traditional folkways began to be lost in the onslaught of the modern media culture. Child ballads gave way to the Top 40; quilts featured cartoon character designs; and the distinctiveness of the region began to erode as it was bombarded by outside influences. In each case "Strange Days" meant the Sixties.

Music is a continuous wellspring of creativity for me. When I was writing the subsequent Appalachian Ballad novels, I would make a sound track for each book, before I began the actual process of writing. The cassette tape, dubbed by me from tracks of albums in my extensive collection, would contain songs that I felt were germane to the themes of the book, and sometimes a song that I thought one of the characters might listen to, or a "theme song" for each of the main characters. Generally, the songs I use to focus my thinking do not appear in the novel itself; they are solely for my benefit, although I have thought of providing a "play list" in the epilogue to each book.

"Her powerful narrative mixes angst-ridden notes from the front, quiet fears over yellowed photographs, and sad songs from the past playing silently in troubled minds." - ALA Booklist Starred Review