New York Times best-seller

Randall Stargill's four son's have gathered at their mountain farm to build a coffin for their dying father. His passing causes a dilemma for his sons, who must come to terms with their dysfunctional family, and also decide what to do with the farm, which has been Stargill land since 1790. Only Clayt, the youngest, a naturalist and Daniel Boone Re-enactor, who loves the land like a latter-day pioneer, wants to save the farm from a real estate developer bent on despoiling the mountain.

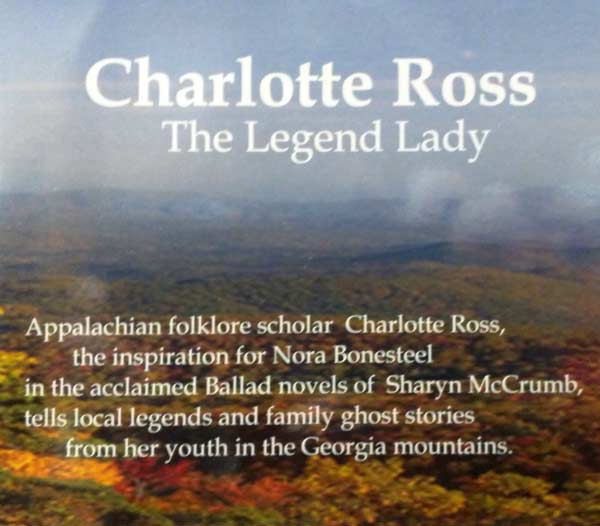

For Appalachian wise woman Nora Bonesteel, Randall's sweetheart of long ago, his imminent death poses another problem: the small box that must be buried with Randall, as she tells his family. When the Stargills open the box and find the bones of a child, Sheriff Spencer Arrowood is brought into the matter, but Nora refuses to say where she obtained the bones, or to whom they belonged. The sheriff dreads charging Nora Bonesteel for murder, even more than he dreads evicting his old friends the Stallards from their farm, which has been bought for unpaid taxes by the same real estate developer who wants the Stargill place.

But land is more than a place to the people of the Southern mountains--land is who they are; as much blood kin as the folks in the family cemetery. Their Celtic forebears were willing to die for the land, as were the Cherokees who came before the settlers. Now the settlers' descendants must lose the land — but, as always, someone will die in the process.

Themes for The Rosewood Casket

Grave of Nancy Ward (Nunyehi), the ghighau (wise woman) of the CherokeeIn The Rosewood Casket, I wanted to talk about the passing of the land from one group to another, as a preface to the modern story of farm families losing their land to the developers in today's Appalachia. The voice of Daniel Boone is central to the novel's message, a reminder that the land inherited by the farm families was once taken from the Cherokee and the Shawnee. The novel begins with Cherokee wise woman Nancy Ward, in the last spring of her life, as she realizes that her people are about to lose the land that she tried so hard to preserve for them. As a reminder of that transience of ownership, in a passage in chapter one of The Rosewood Casket, I trace the passing of the land even farther back: to a time at the end of the last Ice Age, twelve thousand years ago.

Grave of Nancy Ward (Nunyehi), the ghighau (wise woman) of the CherokeeIn The Rosewood Casket, I wanted to talk about the passing of the land from one group to another, as a preface to the modern story of farm families losing their land to the developers in today's Appalachia. The voice of Daniel Boone is central to the novel's message, a reminder that the land inherited by the farm families was once taken from the Cherokee and the Shawnee. The novel begins with Cherokee wise woman Nancy Ward, in the last spring of her life, as she realizes that her people are about to lose the land that she tried so hard to preserve for them. As a reminder of that transience of ownership, in a passage in chapter one of The Rosewood Casket, I trace the passing of the land even farther back: to a time at the end of the last Ice Age, twelve thousand years ago.

Appalachia was a very different place at the end of the Ice Age, when the first humans are believed to have arrived in the mountains. The climate of that far-off time was that of central Canada today, too cold to support the oaks and hickories of our modern forests. Appalachia then was a frozen land of spruce and fir tree, but it was home to a wonderful collection of creatures: mastodons, saber-tooth tigers, camels, horses, sloths the size of pick-up trucks, and birds of prey with wingspans of twenty-five feet. The kingdom of ice that was Appalachia in 10,000 B.C. was their world, and they lost it to the first human settlers of the region, who hunted the beasts to extinction in only a few hundred years.

Losing the land is an eternal process, I wanted to say. It seemed fitting to start with these early residents, as a reminder that even the Indians were once interlopers. Although the title came from a 19th century Tin Pan Alley tune ("The Rosewood Casket"), for me the theme song of the book is "Will the Circle Be Unbroken"?

The supernatural aspect of the book is actually magic realism-- the blurring of the line between the real and the supernatural with the equal acceptance of both. I put this in the book because I find it in the culture itself as an echo of the traditions brought to the region by the settlers from Celtic Britain. You will find the same patterns of second sight and revenants on both sides of the Atlantic.

The family relationships in the book are a microcosm of the dilemma faced by families whose children must leave home to have careers.